If you are measuring pool covers and liners with buckets and tape measurements, how often do you feel something isn’t “right” when you go to install, even though you felt you took “really good” measurements?

Based on our detailed analysis, we have discovered that your measurements could be off by as much as 30” (2 ½ feet) if you have as little as a 2” mistake in the AB bucket locations.

To understand why this can happen, let’s start with how AB measurements work.

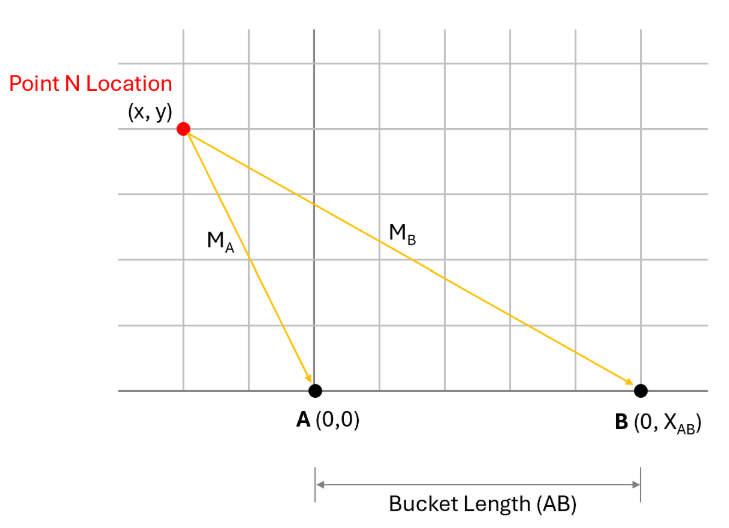

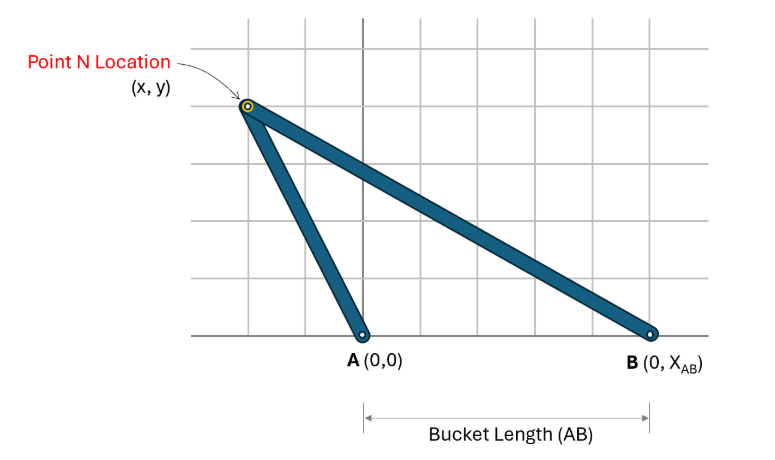

AB measuring relies on simple geometry to determine a desired point’s location in space based on “triangulating” distances from two other “known” points, namely the A and B locations.

If we consider the buckets to be located along the X axis in an X-Y coordinate system, with A centered at (0,0) and B centered at (0, XAB), then any point we measure in space can be determined by taking 2 measurements: MA and MB as shown above. Using the 3 “known” lengths MA, MB and AB, we can easily calculate the (x, y) coordinates of the point and plot on a graph as shown.

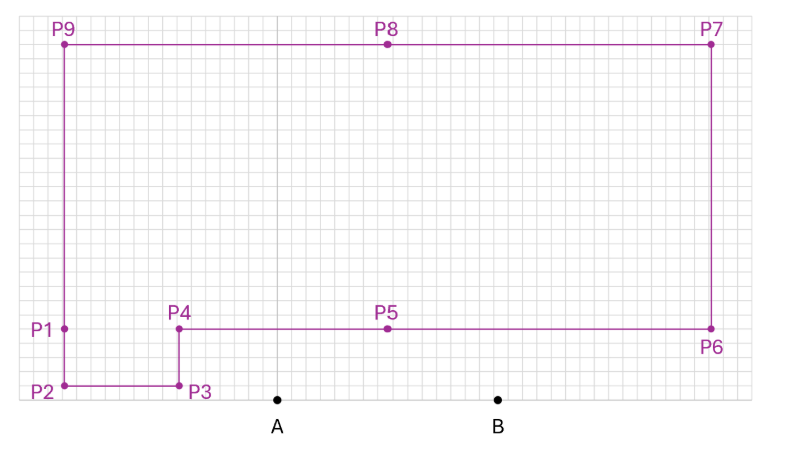

Doing this type of measurement at key points around a pool, you can easily generate an image like the one below, which can be used by manufacturers to create covers and liners for the pool with exceptional accuracy.

BUT, the accuracy of what is built relies on the accuracy of the points captured. The calculation is precise, so all errors are introduced by errors in any or all of the three measurements used (e.g., MA, MB and AB). In other words, the accuracy of any point’s location will be determined by the accuracy in each of the three measurements used (e.g., MA, MB and AB).

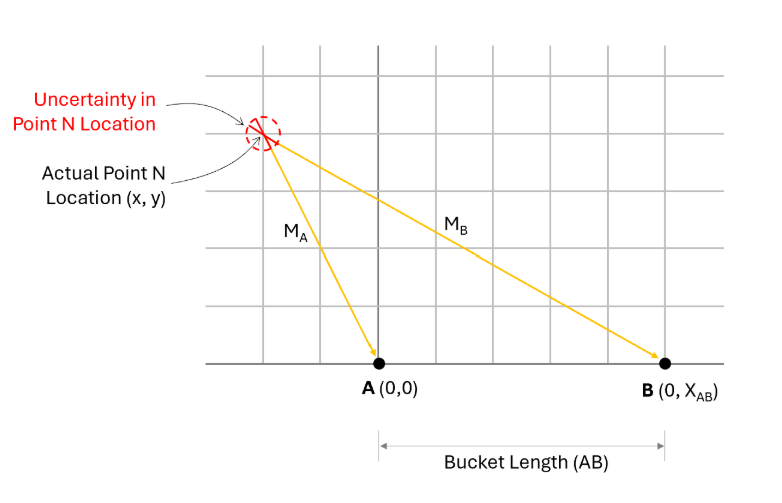

Let’s first consider errors in MA and MB. If MA and MB are slightly wrong, then the location of the point will be roughly off by the same magnitude, in any direction. This can be demonstrated by the “circle of uncertainty” shown in the picture below.

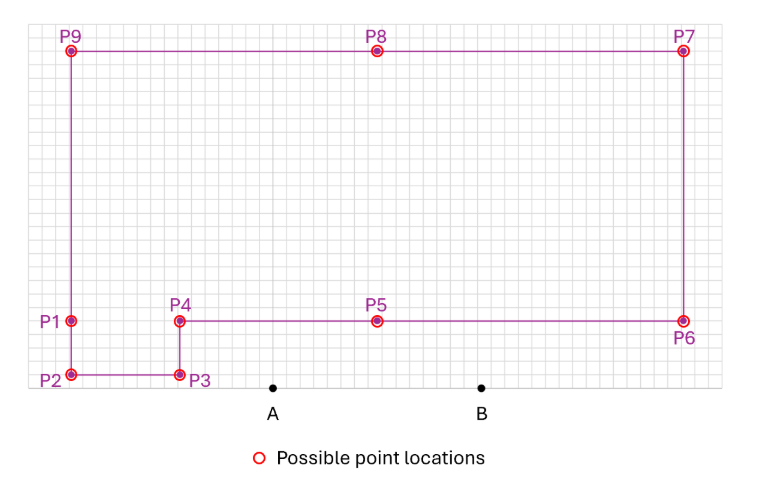

As a concrete example, if MA and MB have errors of roughly ½”, the most you would expect any points’ location to vary would be 1” in any direction. While this is not ideal, it can be managed by taking more accurate measurements to A and B from each point. Also, the error introduced will be “averaged out” over the course of all the measurements, as each will be somewhere within that “circle of uncertainty”, and the overall shape of the pool outline will still be roughly accurate, since over all the measurements, we would expect each to fall within a small range around each “actual” point, as shown below.

As we started with, we determine a point’s location using triangulation with three “known” values. We’ve discussed the errors introduced in two of them (namely MA and MB), now let’s think about the third, the AB distance. Assuming you can take accurate measurements at any distance to AB (which can be difficult for many other reasons using tape measurements and buckets), the real problem is introduced with inaccurate measurements of the AB locations, since those changes are systemic, and impact every point differently.

The other complexity with AB is that errors are introduced in 2 ways. The first is if the AB location is not measured accurately when the AB’s are setup, or it’s recorded inaccurately, so that it differs from “reality” by some amount. The second is that the AB length changes by mistakenly moving whatever is used to determine either the A or B location. If using buckets with tapes attached, this could be caused by pulling on the bucket too hard trying to get the tape taught, forcing it to slide along the deck. Even if you noticed this happened, you may not return the bucket to the exact original location before taking new measurements, resulting in a small change in the AB length.

Both of these issues result in using a value of AB in the calculation that is “wrong”, resulting in incorrect values of X and Y. What we will show is that small changes in AB can have really dramatic effects on the calculated values of X and Y for any and all points.

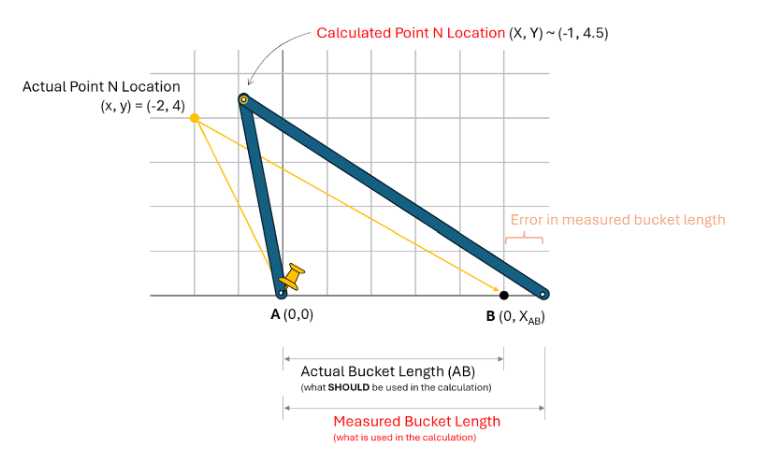

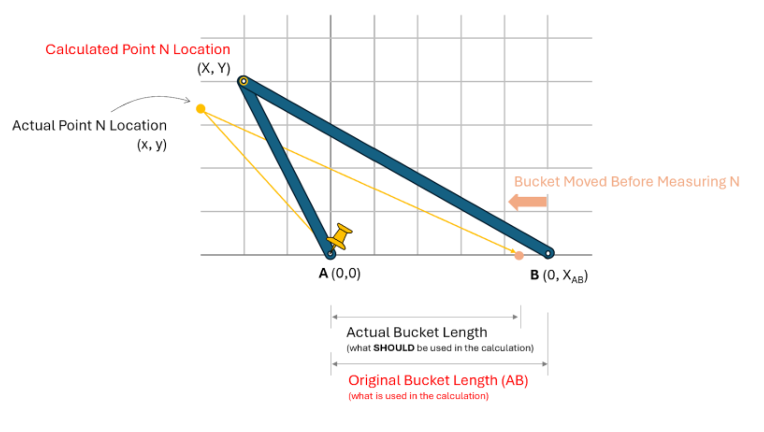

To understand this, let’s consider MA and MB to be fixed (well known) and think about what happens with small errors in AB. This can be modeled by connecting two rigid sticks at one end (where we are measuring the point from), as shown in the following picture.

If we then “pin” the A location, and move the B location along the X-axis, you can see what happens to errors in the AB length.

Let’s first consider the situation where we inaccurately measure the distance between the A and B locations, such that the value we measure is larger than “reality”. This will result in a calculation of the X,Y coordinates of the point as shown here.

Using the actual AB length, the point should be placed at the (x, y) coordinates of (-2, 4). But, since we use a longer length for AB in the calculation (using the same MA and MB) values, we actually calculate (x, y) to be about (-1, 4.5), which is much different from “reality”. You can see the calculated value is “pulled” to the right as the B location slides to the right.

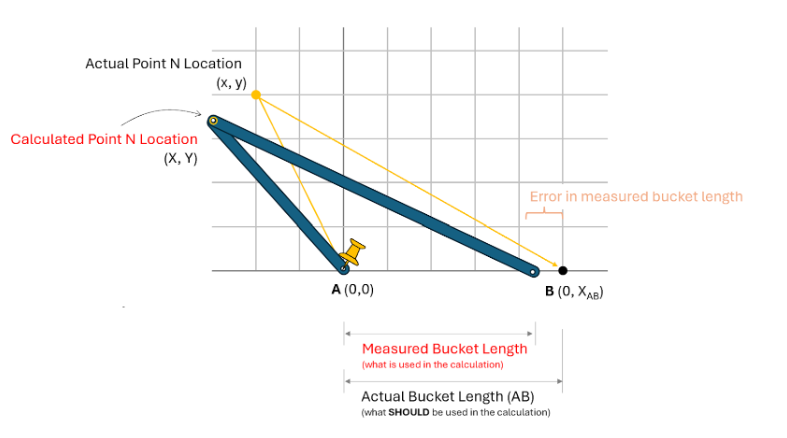

This is true if we go the other way as well, just the opposite. If we consider the case where we measure AB to be shorter than “reality”, we get the following.

Here, since B is moved to the left, it pushes the pivot point left and down, and results in an inaccurate measurement as well.

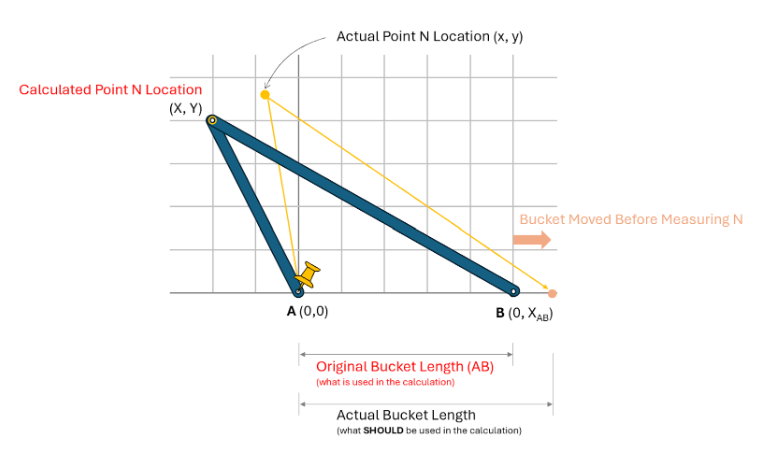

This effect is identical if we move the bucket after measuring its AB separation length, and we have the following two examples. The first shows the bucket moving to the right.

And the second shows the bucket moving to the left.

So all of these show that incorrect measurements of AB, just like MA and MB, result in incorrectly calculated point locations. What may not be obvious in these pictures is the magnitude of change. The change in total distance from the actual point to the calculated point can sometimes be much larger than the shift in B, and this varies depending on where the point is located relative to A and B.

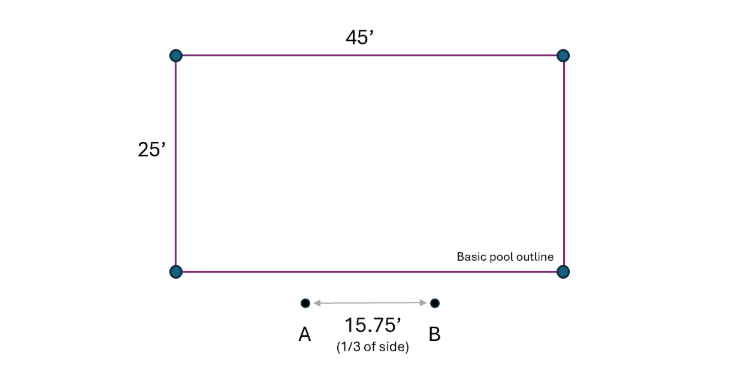

To determine the possible amount of changes, we started with a simple pool outline calculated “precisely” for a 20’ x 45’ pool, using buckets separated by 15’ feet centered on the pool at 3’ from the edge. The original drawing looked as follows:

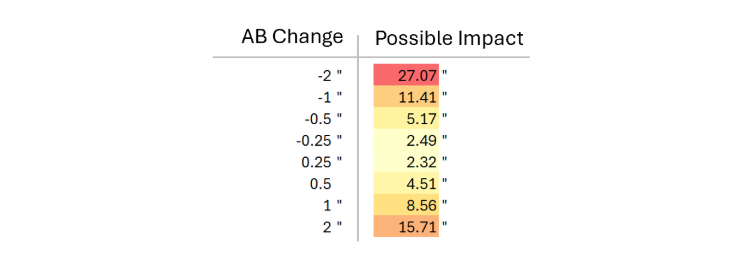

Then, we calculated what would happen if AB was wrong by different amounts using the precise values of MA and MB. The results of this analysis are as follows:

This shows that if AB is wrong by as little as ¼”, you will see some points off by at least 2 ½”. Even what may seem like a small change of ½” will result in some points being about 5” off. This may be OK for some situations, but for pool liners, this will definitely result in the liner not fitting properly, especially at the steps and seams. BUT, if you somehow have AB wrong by only 2”, you will have at least one point 27” away from its actual location which would result in a cover or liner that doesn’t fit at all.

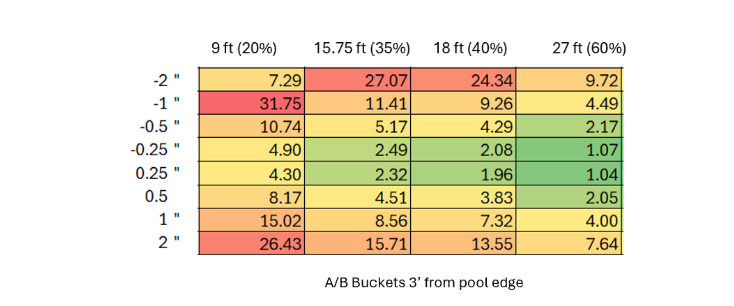

We took this a step further and ran many more possibilities, resulting in the table below:

The columns represent different AB lengths (bucket separations), and the rows are the amount of error introduced in measuring AB length. You can easily see that small changes in error in AB result in large movements of the calculated point from the actual point.

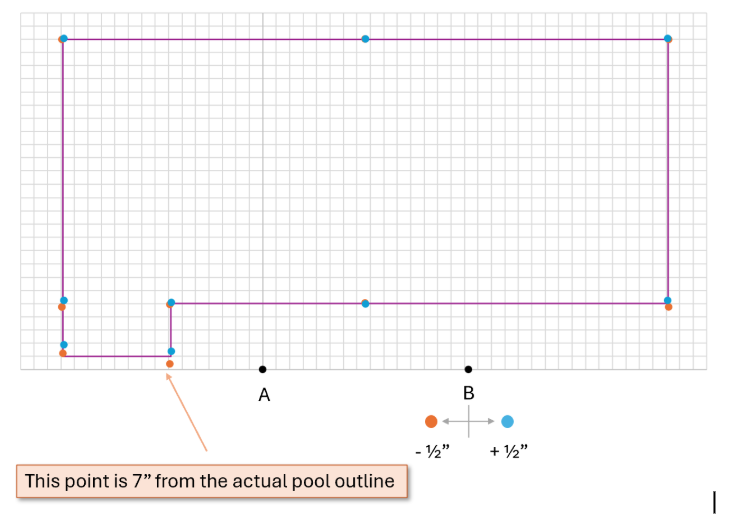

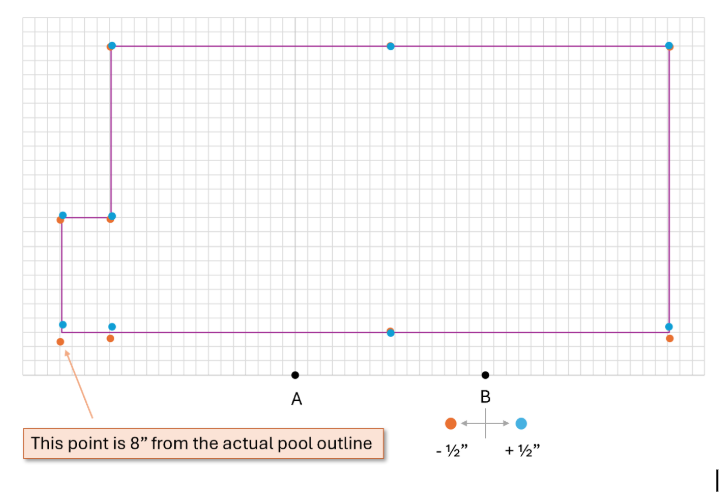

To see this visually, we applied the same method to two pool situations with steps. The blue dots represent the calculated value using an AB that is ½” too big, and the orange dots are using an AB that is ½” too small.

In each of these cases, for a 20’ x 45’ pool with a 4’ x 8’ step setback, you see some points in the step area off by 7 or more inches. This is a BIG deal if you want the liner to fit!

So what does this all mean?

First, you should do everything you can to reduce errors in measurements.

Second, you need to measure the distance between A and B as closely as possible, and make sure it doesn’t change.